THE RETIREMENT CRISIS IN SOUTH AFRICA

From inflation oversight, late savings, ‘bad’ investor behaviour, and even being too generous to your adult children — the odds are stacked against the successful retirement of South Africans.

We have seen the statistics about how South Africans do not make sufficient provision to retire successfully. The figure that is most often used is that only 6% of people can retire financially independent. While this is true, other factors also contribute to a worsening retirement situation for many.

Some of these factors include:

Investor behaviour

Underestimating the impact of inflation

Investing too conservatively

Being too generous in retirement

Before we get stuck into some of the factors mentioned above, consider the following facts:

South Africans have the lowest household savings rate in G20 countries.

42% of South African households have no formal retirement provision.

45% of South African retirees are dependent on family.

32% of South African retirees are forced to continue working.

17% of South African retirees are dependent on the state pension.

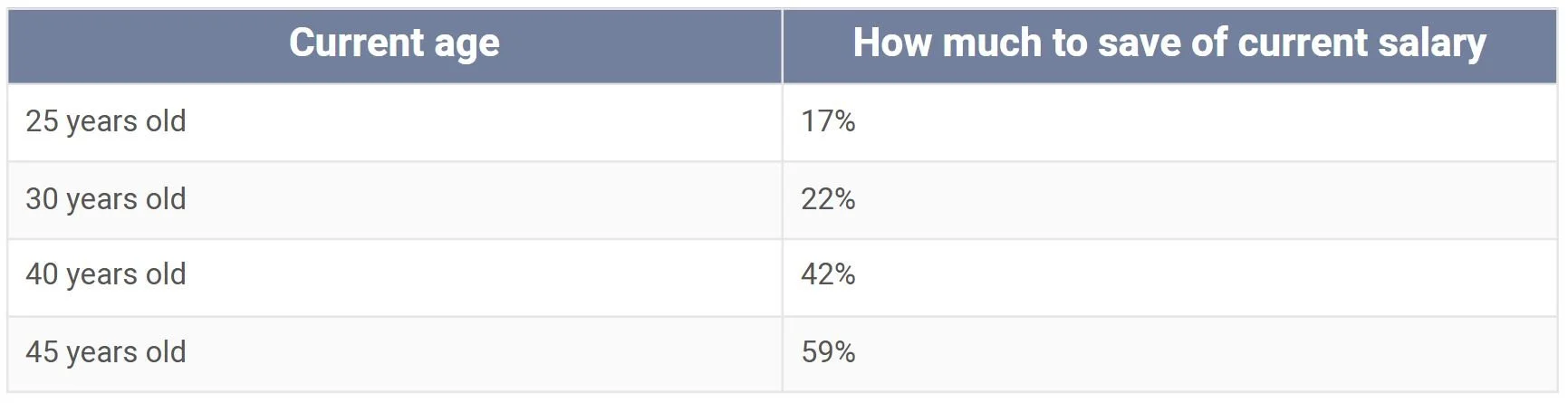

To aim for an income of 75% of your final salary, the following contributions must be made if you start from a zero base:

From the above, we can conclude that the longer you wait to start with retirement provisioning, the harder it gets to reach the 75% replacement objective. It is also clear that one cannot rely only on employer retirement funds. More savings are needed.

Investor behaviour

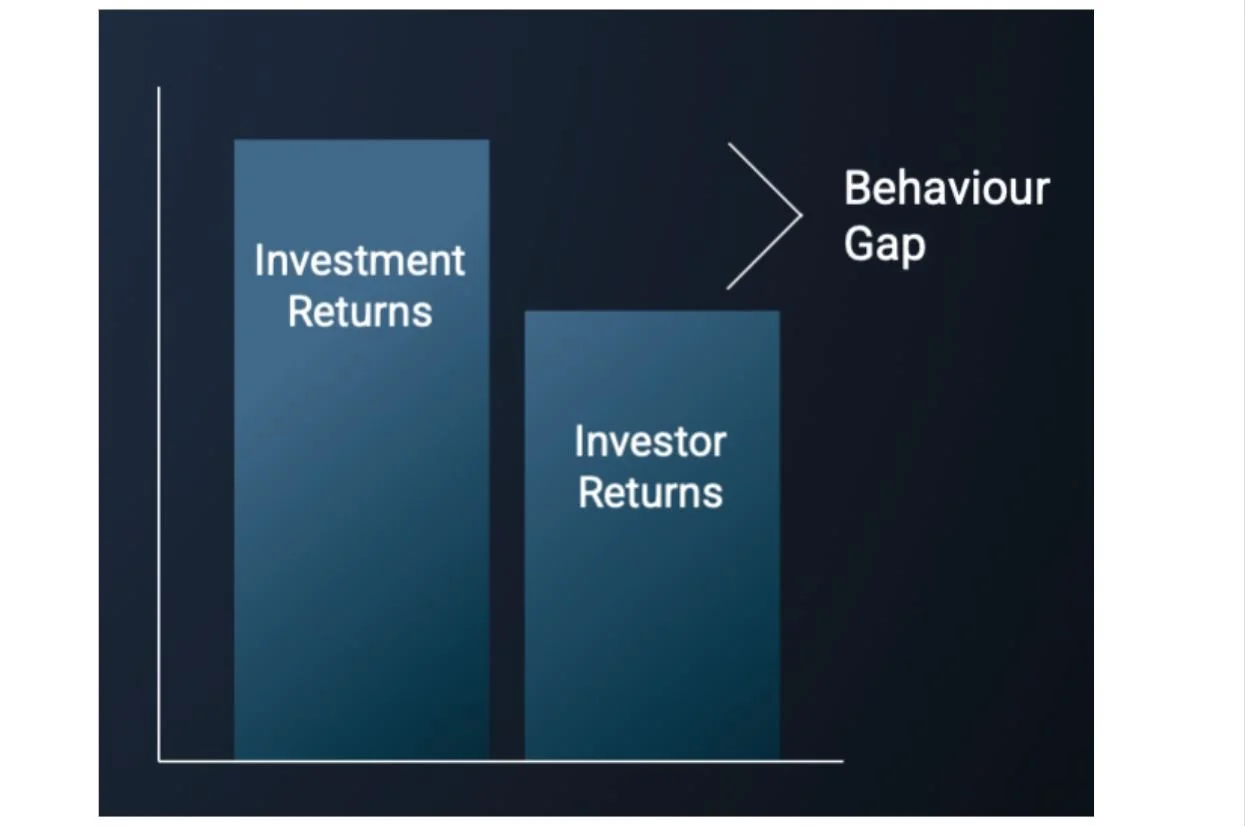

By now, some readers would have come across the Carl Richards illustration that shows how, across the globe, investors underperform the actual funds that they invest in.

Why? Bad investor behaviour. Investors are erratic and their behaviour is driven by emotions, which often leads them to invest and disinvest at exactly the wrong times. Typically, investors invest when markets are exuberant and sell when markets are depressed. Buying “high” and selling “low” can only impede long-term returns.

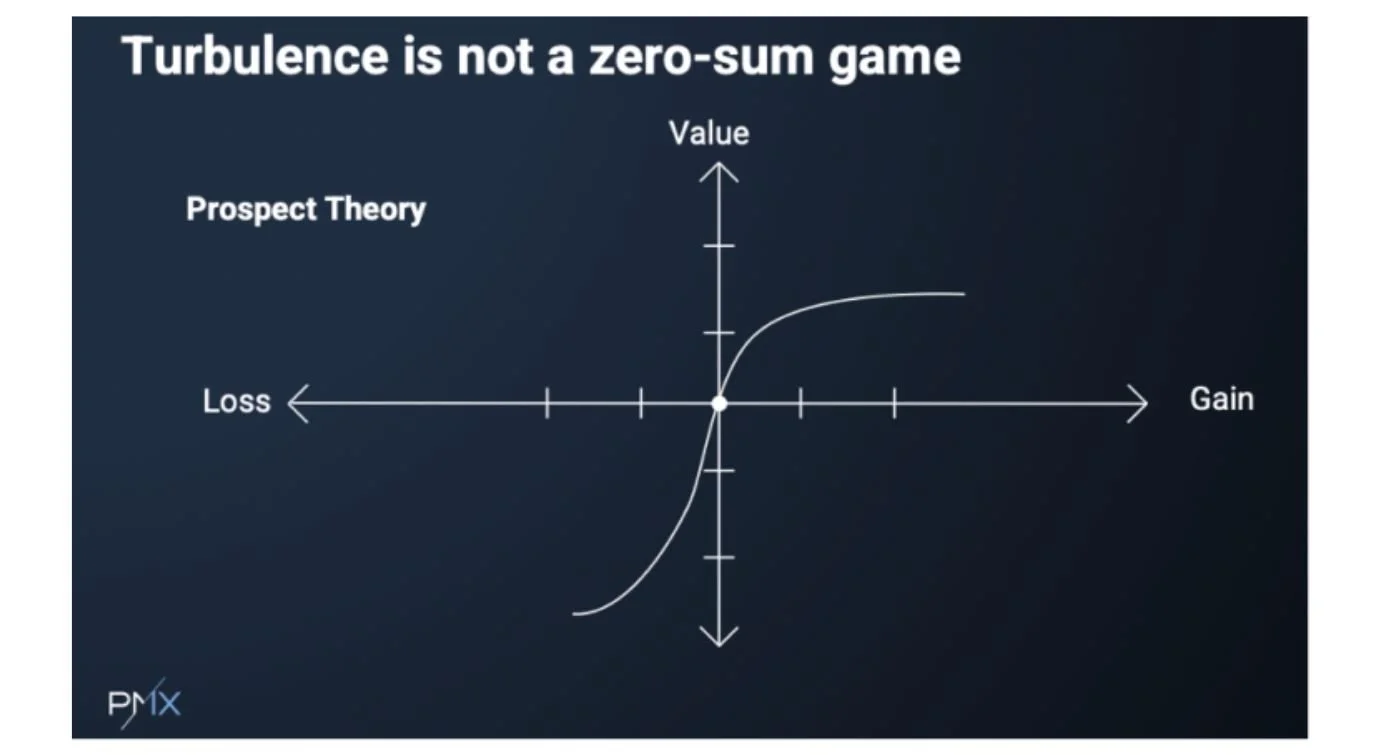

The above illustration and result are due to how investors experience volatility. Volatility refers to investment values that move upward as well as downward. Behavioural finance shows that individuals experience losses much more severely than they experience exuberance. In simple terms, a portfolio that loses 10% in value hurts much more than the joy one gets from a portfolio that grows by 10%. People don’t like losing money! Unfortunately, volatility is often confused with a loss. Behaviour cements volatility into a loss by moving out of a fund while it is in a downward cycle. When it’s time to top up investments due to lower prices, many people turn their backs on them, making the most basic and common investment mistake.

While investors are still in the wealth accumulation phase, volatility is their friend. When drawing income against investments, a slightly different strategy must be applied, but the principles remain the same.

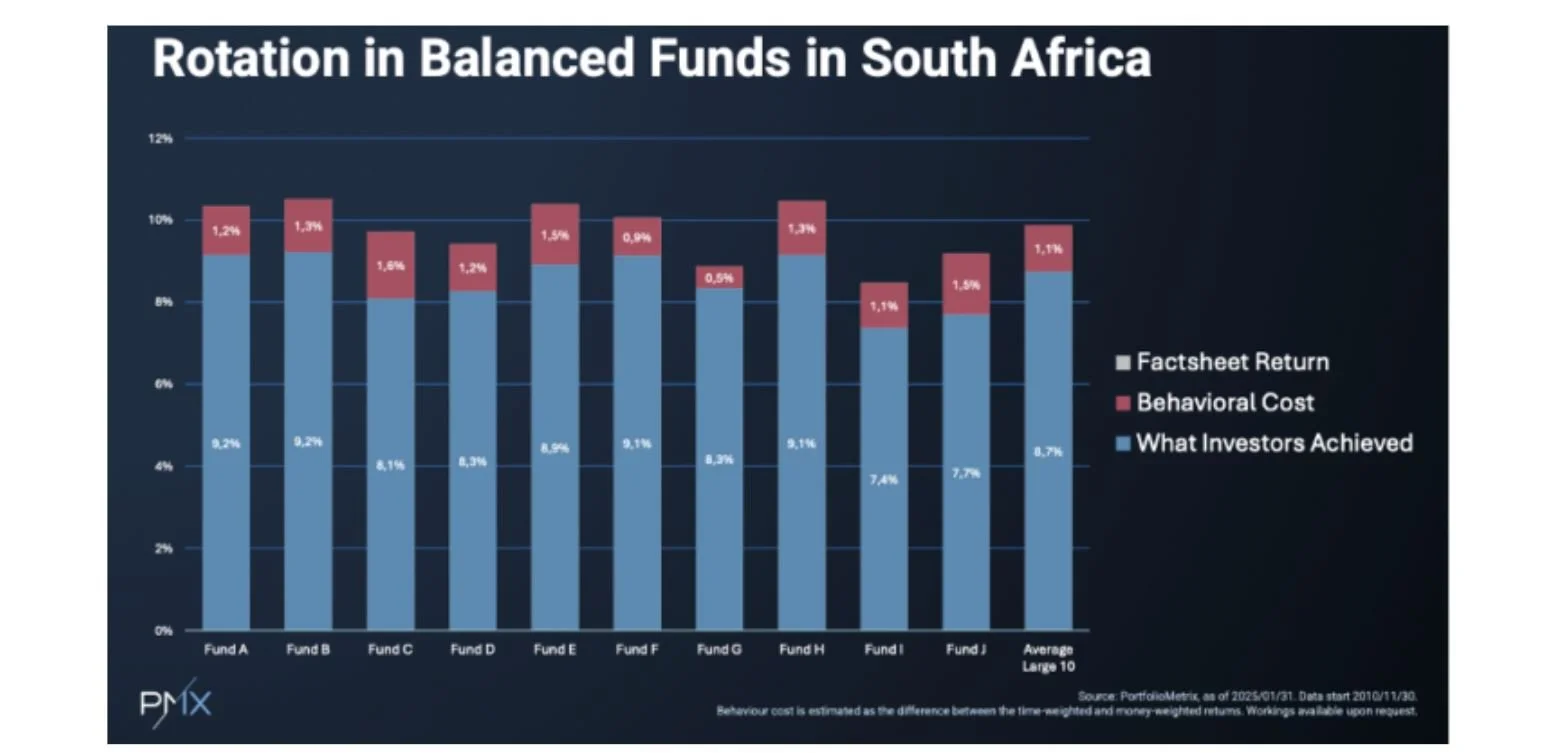

The diagram below illustrates the outcomes of 10 well-known balanced funds, which were analysed to determine the relationship between the funds’ returns over an extended period and the earnings of their investors in the same funds during the same investment period. The trend to switch to cash when markets become volatile and switch back when it is “safe” to do so again, resulted in an underperformance on average of 1,1% per year over 15 years. Simple math without compounding shows that over 10 years, this trend leads to 11% less capital for direct investors than fund returns, and 22% less over 20 years. The gap in global funds is even larger, and many retirees have an investment horizon of more than 20 years.

Underestimating the impact of inflation

Much has been written about inflation in the past. Investors often fall into the trap of oversimplifying their calculations when determining their regular income, based on the returns of their investments. Quick test: If an investment provides returns of 8% per year, is it safe to draw 5% income per year and keep track with future inflation of say 6%?

Two common mistakes are often made in the above scenario. The first mistake is assuming that the portfolio needs to return 11% (5% + 6%) to meet the above objective.

The second mistake is that 5% income is below 8% return, so capital growth is guaranteed.

The truth is that if income is drawn at 5% and increases at 6% per year, while the investment returns 8% per year, the capital value will peak in year 11 and start reducing to nil in 25 years. The reality is that inflation in advanced retirement is probably closer to 10% due to medical expenses. If the 5% income escalates at 10% per year, the capital value will peak in year six and be depleted in 17 years. If this scenario is realistic, a return of approximately 13% per year will be required to maintain income for 30 years while capital will halve over the same period. If living annuity limits apply (maximum 17.5% income drawn), income will start to reduce after 24 years.

Investing too conservatively

From the above, it can be derived that if you intend to draw more than 5% income per year and escalate future income at any rate above 6%, then returns of more than 10% per year are crucial. Lower returns will lead to guaranteed failure. Suppose you are adamant that your investments must be more conservative (less volatile), in that case, you should consider how to manage a lower future income or discuss potential financial assistance with family members.

From the above, we can also conclude why much reference is made to the 4% rule. If you limit your income drawn against investments to a maximum of 4% per year, and future escalations to 8% per year, then a 9% return will provide you with income for 28 years.

From the above, we can conclude that low equity multi-managed funds and Income Funds will only be sufficient if you plan to draw less than 4% income annually. In most cases, the only way to withstand lifelong income pressures is to increase exposure to growth assets both locally and offshore.

Moving to compulsory life annuities when you age versus when the annuity rate justifies it, is another option.

Unfortunately, when markets become more volatile, there is a rush out of growth assets into more conservative funds and Income funds.

The decision to disinvest from a growth fund is an easy one. The difficult decision is when to get back into “the market”. Generally, investors wait until the market moves upward again before dipping their toes back into the market. By the time their funds have vested, the bulk of the upward movement has taken place and voila! We have the behaviour gap.

Being too generous in retirement

This is always a touchy subject. But being a good parent does not mean that you must short-change yourself to help children and other family members. Too often, we experience situations where parents, in trying to do the right thing, cause financial hardship on themselves and family disputes between siblings. If your financial situation justifies handouts, then do it. But please be a bit selfish and think about yourself first before you start with handouts.

This will prevent you from having to look someone else in the eye for financial assistance. The chances are that the people you helped when you could, would not be in a position to help you when needed. We often hear the comment by a child that a parent should have made better provision for retirement, but forget how that parent helped the child in times of need (or want).

Lastly, don’t fall for the “lower fees provide better returns” nonsense. One of the prominent “passive, low-cost” managers lodged a complaint because I mentioned them by name in a previous article when I pointed out their “low-cost” fund’s mediocre returns when compared to “expensive” funds. My comments were prompted by their constant comments about how high fund manager and advisor fees erode returns, and that investing directly with them will provide a better outcome. Fortunately, the editor of this publication sided with me.

Pay managers for what they do, and the same applies to financial advisors. If your financial advisor can keep you on track and help you achieve your objectives, you will be much better off than just bargain hunting. Having a thinking partner on your side who can help you navigate the financial storms that crop up now and then cannot be measured in only fees. I am all for passive low-cost funds, and we use them often, but for the right reasons and achieving better returns is not one of them, especially not in the South African environment.

I am happy to expand on my comments above with examples (and fund manager names) in a future article. And a forewarning to my cheap friends, my comments and figures quoted are public knowledge, as illustrated by Morningstar, not thumb sucking.

Retire well and don’t panic. Stay invested. Proper fund selection and diversification will save you many headaches.

Take care.